We need to set aside the messianism, ethnocentrism, and xenophobia in favor of a Jewish statehood that is rooted in Jewish identity yet suited to the modern world.

How did it come to pass that more than 500,000 “nice and normative” religious Zionists awarded the “Religious Zionist” party with its 14 seats in the Knesset? If we are to remove this shameful stain (and I believe that coercive intolerance and racism are stains) from upon our community and indeed from upon our country, we have no choice but to cast our gaze inward and ask the difficult question: “Does the traditional religious Zionist ideology lead to the current shameful outcome?” And if it does, is that inevitable, or is there an alternative path for the religious Zionist community?

The Religious Zionist Party’s leaders have a xenophobic, hateful and anti-Zionistic ideology. I conclude this based on past declarations both before and since the elections. For example, in response to the 2015 incident in Duma in which a Palestinian family was murdered by a Jew, Betzalel Smotrich stated that the murders were not acts of terrorism and the authorities should treat it as a regular crime. In another instance, Smotrich compared the government’s evacuation of Amona to rape: “When a woman is raped, she suffers. What the government is doing to us is rape,” he said.

Most outrageous of all was Smotrich’s defense of segregating Jewish and Arab mothers in maternity wards in Israel. He actually said, “My wife is not racist at all, but after she gives birth she wants to rest and doesn’t want to be bothered by the revelry of the Arab families.”

We are hearing voices from inside the list that condemn “progress” and call for despotic religious coercion and discrimination between Jews and non-Jews in the medical system (it is hard for me to imagine that most of the supporters of the Religious Zionist party endorse these views)

A final illustration of just how far the party has gone off course is the fact that a disciple of Meir Kahane, whose own racist views made him a political untouchable by the established religious Zionist leadership, featured front and center in these elections. Kahane infamously introduced racist anti-Arab legislation in the Knesset that eerily resembled the Nazi Nuremberg Laws.

To respond to the original question above, we need consider the core ideology with which the bulk of the normative religious Zionist community was indoctrinated: the triad of the People of Israel (Am Yisrael), in the Land of Israel (Eretz Yisrael) according to the Torah of Israel (Torat Yisrael).

When these seemingly unassailable values are signposts of individual conscience and commitment, they are innocuous enough, and may even be a source of inspiration and a call to altruistic action. However, assigning these values to a modern nation-state with aspirations to craft public and foreign policy is very dangerous, and that is what this “youth movement” ideology has unwittingly done. It betrays a total lack of understanding concerning the nature of the State of Israel as it was conceived of by its founders and indeed by the vast majority its inhabitants.

I wish to look at each of these principles separately and show how they stand in direct conflict to the Zionist project and undermine the State of Israel, but I must first establish why I, a religious Zionist myself, believing we answer to a “Higher Authority,” also believe the nature of the state should be determined by the original conception of its founders and the majority of its inhabitants, even though Israel’s secular institutions (like the Supreme Court and the Knesset) and its processes (like democracy, international law, and negotiated agreements) are all humanly legislated.

Rabbi Isaac HaLevi Herzog, the first chief rabbi of Israel, recognized clearly the nature of the state. Relating to freedom of worship and minority rights, such as the right to vote and be elected to office, he wrote,

The foundation of the state itself is a partnership of sorts. It is as if, through negotiations, we reached agreement with gentiles that they would allow us to establish a joint government which grants the Jews superiority in certain areas and that that state shall be called in our name. (Constitution and Law in a Jewish State According to the Halacha, vol. 1, 20)

Rabbi Herzog understood that the foundation of modern Israeli sovereignty is not derived from God’s promise to Abraham or similar biblical narratives. He acknowledged that this modern state was different from the Israelite sovereignty (Malkhut Yisrael) in the days of David and Solomon, as well as the earlier state, when the Israelites entered the land of Canaan. Rather, the sovereignty is legally and halachically based upon the outcome of the negotiations which the Zionist movement (as the recognized representatives of the Jewish people) conducted with international bodies. The status of the international agreement, Rabbi Herzog maintained, is that of treaty between the nations and Israel; a brit or a covenant – not that of biblical Israelite dominion.

Rabbi Yehuda Amital, the rosh yeshiva and founder of Yeshivat Har Etzion, shared this view. I often heard him invoke Maimonides’ reading of the Israelite covenant with the Canaanites of Giv’on (see Joshua 9), which emphasizes the prohibition to violate covenants with gentile nations (Laws of Kings 6:5), in the context of Israel’s obligation to guarantee human and civil rights to all its citizens. Rabbi Amital maintained that the guarantee protection of democratic rights to non-Jewish minorities in Israel’s Declaration of Independence was halachically binding, as a covenant with the non-Jewish inhabitants of the country.

For those who prize halacha over and above international law, the upshot here is that the terms and conditions that the Zionist movement and the subsequent State of Israel agreed to, not only as obligations, but regarding the nature of the state itself, are halachically binding. That is why the intent of the founders and the outcome of the negotiations in which they engaged determine the nature of the country.

It is against this backdrop that I maintain that adherents of the “triad” ideology of the People, Torah, and Land of Israel, who see themselves as super-Zionist, actually undermine the Zionist project and the modern State of Israel.

The People of Israel

The assumption is that Israel, as a Jewish state, is the embodiment of the Jewish people, which makes Jews privileged members of that state. The sovereignty of the State of Israel is therefore “Jewish sovereignty,” and a continuation or even a reincarnation of the Kingdom of David and Solomon. But if the conflation of Israeli and Jewish sovereignty were true, then all Jews from Teaneck to Timbuctoo would automatically be Israeli citizens. The fact is that Israel, even with the Law of Return, which entitles Jews to become citizens of Israel, does not grant Jews the world over automatic citizenship. As much as the nature of the Jewishness of the State of Israel needs to be hammered out, these assumptions are simply false.

Belonging to a modern nation-state is based upon citizenship, and not on ethnic or tribal kinship. Calls to treat non-Jewish citizens of the state differently, therefore, undermines the nature of the state and paradoxically reverts back to the Diaspora reality, where Jewish peoplehood was organized around family and community. This is particularly ironic since the advocates of the “triad ideology” often condemn the ideologies that they deem insufficiently nationalistic as being “galuti,” – exilic, or suffering from an inferior (to their minds) Diaspora Jewry attitude.

The Land of Israel

The justification for the establishment of a Jewish state in Palestine was certainly based upon the historical bond between the Jewish people and the land of Israel, as per the position established by the League of Nations at the 1922 San Remo Peace conference, but once the state was established, its borders were established according to the area over which it exercised sovereignty, and not historical affinity or religious/messianic aspirations.

In a sense, in 1948, the historical/religious dream called the Land of Israel was supplanted by the political reality of the State of Israel. As Jews, we certainly maintain our religious and cultural connections to the historic land of Israel but the political entity that the land might have once housed has given way to the state.

The Torah of Israel

Religious beliefs are intensely personal – between oneself, one’s conscience, and God (if one believes in God). This awareness forms the basis of separation of church and state in democratic regimes to one degree or another. Government has no business legislating in that sacred space.

The fundamental misconception of the sovereignty issue has led to radically unbalanced swings in attitude towards the state, with very damaging consequences.

Its roots are in the opinion expressed by Rabbi Zvi Yehuda Kook (son of the first chief rabbi in Palestine prior to Israeli independence, Rabbi Abraham Isaac HaCohen Kook): “There is one primary, general thing: the state. It is all holiness and without flaw. It is a supreme heavenly manifestation of ‘He who returns the divine presence to Zion.’” Rabbi Zvi Yehuda’s mystical messianic fetishization of the state became the foundation of the uncompromising ideology and political agenda of Gush Emunim of the 1970s and ‘80s.

Yet this messianic veneration of the state — to the degree of idolization — was always destined to be smashed. The unforgiving reality of withdrawals, disengagements and compromises simply contradicted the fantasy. Rather than grapple with the challenges, however, the shards of the idol took the form of ethnocentrism, xenophobia, and the paranoid “everyone is against us” mentality (this last characteristic becoming a self-fulfilling prophecy).

The Oslo Accords and the Disengagement from Gaza were perceived as retreats from the unalterable process of redemption (the late Rabbi Mordechai Eliyahu proclaimed that the Disengagement would “never come to pass”) and deep despair and disappointment engendered a nativist right wing movement that is characterized by alienation from the state and hostility toward its institutions. It is not by chance that Smotrich and Itamar Ben Gvir enjoy greater common cause with the anti-Zionist Haredim than with secular Zionists.

An Alternative

But there is another way to think about our Jewish statehood, one that is firmly rooted in our identity as Jews. It also has the advantage of being suitable to the modern state in which we live.

Years ago, my wife and I visited the predominantly secular artist village of Ein Hod near Haifa. We were graciously invited to tea by the family of a well-known artist who owned a gallery there. I remember that we were trying to ascertain what common basis of identity we shared with our hosts. I asked them, “When I say ‘Avraham avinu,’ does that resonate for you? If I say ‘Har Habayit’ or ‘Ma’amad Har Sinai,’ does that mean anything to you?” They responded with a resounding yes. I walked away very encouraged about the fate of our common future, and I realized something important about our shared identity in the present: what made us related, part of extended family, is the shared stories we tell about ourselves. Just as when I get together with a cousin, we share the stories of our common aunts, uncles, and grandparents, so too when we gather with fellow Jews, we share common narratives.

What characterizes these narratives is their fluidity and non-coercive nature. Within different branches of the family, there are often differing versions of the same stories, and it is near impossible to determine which version is historically accurate. But, historical accuracy is not the point. Rather, at the core of the differing tales, we recognize that we are talking about the same grandparent or aunt. The significance of the stories lies not in their historical accuracy, but in how they constitute identity and a feeling of belonging.

The ground my wife and I shared with our hosts was the common narrative that constitutes shared culture and identity, and not our religious beliefs or commitment to ritual. That shared common ground shared by all Jews should be the basis of what constitutes the Jewishness of the state: identity based upon culture, not religion. Religion is intensely personal and needs to be kept far from the state’s authority. Culture, however, is profoundly constitutive of identity and is an appropriate expression of Jewishness for a modern democratic nation state.

I propose a transvaluation of “the People of Israel in the Land of Israel according to the Torah of Israel” into the “Citizens of Israel, in the State of Israel, according to the sovereign laws of the state, as legislated by the democratically elected parliament of Israel.”

Religious Zionists need to reconnect with the stories we tell about ourselves in the Bible, and the passionate ethos of the prophets. We need to remember and teach that the founding narrative of the Jewish people is that we were oppressed in Egypt so that we should possess empathic compassion for the strangers, the weak, and the downtrodden. We should feel the revulsion of the prophets in the face of corruption and decadence, and we should quake when we read their call for justice for the widow and the orphan.

If, and it is a big if, we can meet this challenge, we shall purge the stain from our community and our country and approach the aspiration of which we claim to be so worthy, to be a light unto the nations.

This article was originally published in the Times of Israel in January 2023

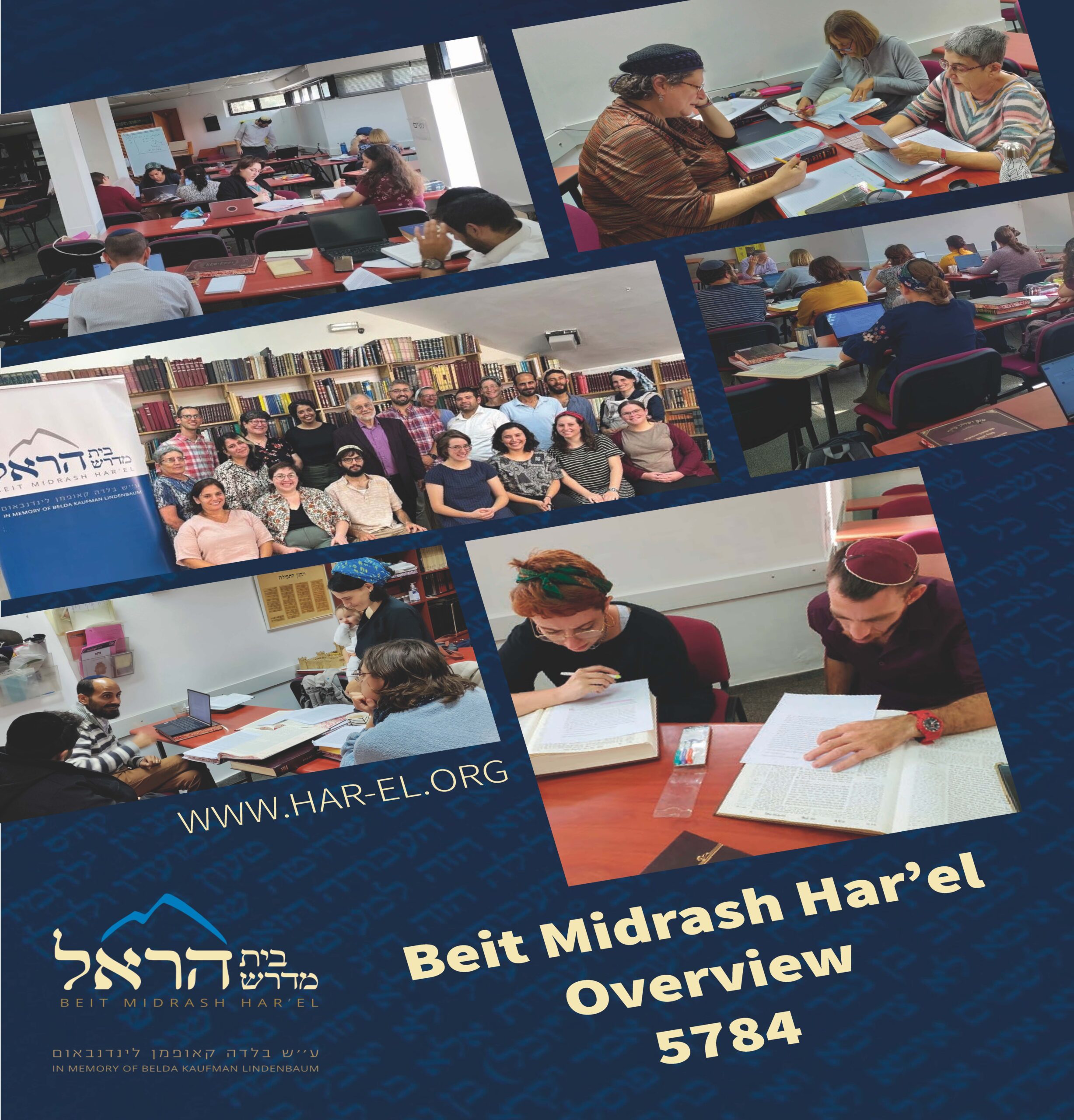

Rabbi Herzl Hefter is the founder and Rosh Beit Midrash Har’el in memory of Belda Kaufman Lindenbaum, in Jerusalem. It is a beit midrash for advanced rabbinic studies for men and women. He is a graduate of Yeshiva University where he learned under the tutelage of Rabbi Yosef Dov Soloveichik זצ”ל, and received smikha from Rabbi Aharon Lichtenstein זצ”ל at Yeshivat Har Etzion where he studied for ten years. Rabbi Hefter taught Yoreh De’ah to the Kollel fellows at the Gruss Kollel of Yeshiva University and served as the head of the Bruria Scholars Program at Midreshet Lindenbaum. He also taught at Yeshivat Mekor Chaim in Moscow and served as Rosh Kollel of the first Torah MiZion Kollel in Cleveland, Ohio. He has written numerous articles related to modernity and Hasidic thought. His divrei Torah and online shiurim can be accessed at www.har-el.org