My very assumption of this new role embodies Yeshayahu Leibowitz’s ideal that halacha adapt to suit a radically different reality – but he wouldn’t approve of all my ideas.

Shayna Abramson Kovler receives semikha from Rabbi Herzl Hefter and Rabbi Dr. Daniel Sperber in Jerusalem, ceremony MC-d by Rabbi Elhanan Miller. (photo: Arieh Kovler)

“And He, the Merciful One, atones iniquity; and does not destroy. He frequently withdraws His anger and does not arouse all His rage The Master, deliver [us!] The King will answer us on the day we call.”*

These words, from the Maariv prayer, have been echoing in my head for the past few days.

That is because a few days ago, I became a rabbi.

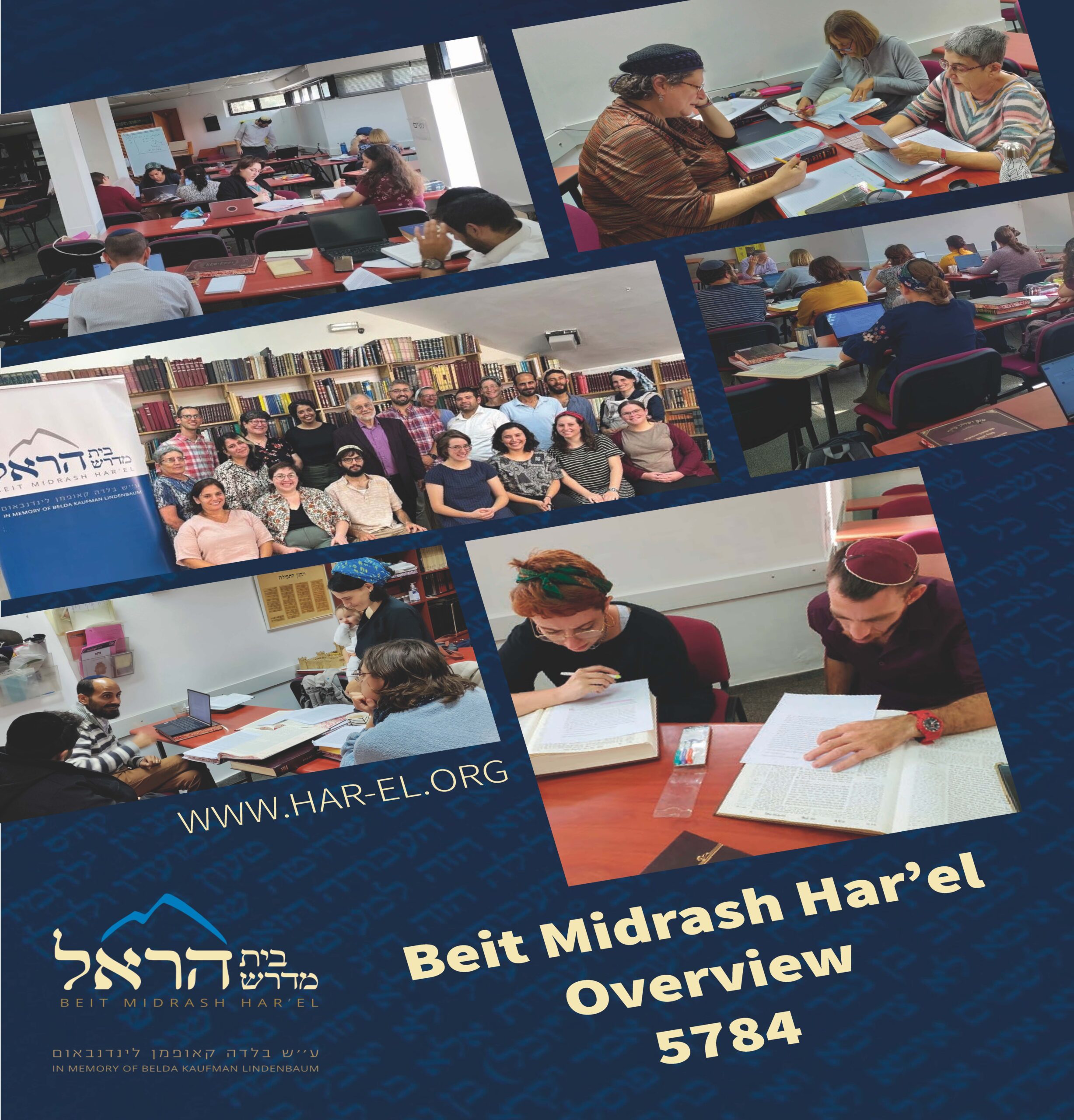

I stood on stage with my fellow students from Beit Midrash Har’el and was ordained by our mentors and teachers, Rabbi Herzl Hefter and Rabbi Dr. Daniel Sperber.

And I’m still trying to figure out what that means. What does it mean to be a rabbi today? What does it mean to be a rabbi who is a woman? What does it mean to be a rabbi in Israel?

So I keep on going back to those lines in Maariv — because there is one sublime moment, after Yom Kippur. The shofar has been blown, the song, “Next Year in Jerusalem,” has been sung. We take a deep breath — and we say these words of the Maariv prayer that signal that Yom Kippur is over and the day after has begun. We say these words, and begin the transition into the rest of the year, starting the cycle all over again.

“And He, the Merciful One, atones iniquity; and does not destroy. He frequently withdraws His anger and does not arouse all His rage, The Master, deliver [us!]. The King will answer us on the day we call.”

Dr. Yeshayahu Leibowitz saw this moment as emblematic of the Jews’ relation to halacha: we express devotion to God by fulfilling God’s law, with all of its regularity, and that is symbolized by the return to weekday Maariv as soon as Yom Kippur is over. We say the normal weekday words about atonement, only moments after the Day of Atonement is over, because the goal of Yom Kippur is not a change in spiritual state; rather, we are to spend 25 hours in prayer because that is what God commanded us to do, and it is by carrying out those commandments that we worship God. When Yom Kippur is over, we go back to weekday Maariv, because that is what halacha demands. Saying those words when they have no meaning carries its own form of meaning, because it constitutes an act of worship, as I sublimate my will to the Divine Will.

I think that model can be extremely powerful when we are observing a halacha that we struggle with emotionally. The model that posits observance itself as a religiously meaningful act, even when we do not find meaning in the content of the halacha, can validate our emotional struggles with halacha: It is okay to not enjoy the individual halacha in question (indeed, Yeshayahu Leibowitz would argue that if we observe halacha for our own enjoyment, then that defeats the purpose). The fact that we kept halacha despite our lack of enjoyment is its own form of worship.

But this model is not very powerful when proposing a mode of committed religious observance that incorporates halacha into a larger search for connection with God.

For me, the moment when the shift from Yom Kippur to weekday Maariv happens is one of the most powerful moments in the year, but in a way that reflects a vastly different model for relating to halacha.

When I say those words, I realize that I am tasked with taking the spiritual energy I feel from engaging in 25 hours of introspection and prayer on the Day of Atonement, and integrating it into my everyday routine — and it is the integration of the spiritual energy from Yom Kippur into my everyday routine that reveals the true power of the day. Yom Kippur is a day of redemptive spiritual potential whose worth is measured in the way that we actualize that potential once the day is over.

That is how I feel right now. The ordination ceremony on Sunday gave me an incredible spiritual feeling, and three years of beit midrash study gave me many resources, as I studied Torah and was inspired by my teachers and fellow students. Now it is up to me to take that energy, and to integrate it into my routine so that I can share my Torah.

I am honored to be part of a movement that advances halachic commitment alongside commitment to recognizing the unique image of God in every person, understanding that commitment to halacha is part of a larger endeavor to worship God that must include respect for God’s creations.

I also know that this project is in some ways antithetical to Dr. Yeshayahu Leibowitz’s approach to Jewish law and morality (as my teacher Rav Herzl Hefter so eloquently pointed out in his speech at the ordination ceremony).

But that doesn’t mean that I am ready to give up on Dr. Leibowitz’s teachings. I believe it is important to have different models that can work for different people at different moments of their lives, and sometimes, “these and these are the words of the living God.”

With the words of Maariv echoing in my head, I felt a need to re-read his thoughts about the transition between Yom Kippur and Maariv, so I picked up some of his writings, and stumbled across this paragraph:

“Barring women today from Talmud Torah segregates Judaism from the spiritual reality shared by Jews of both sexes. This is likely to break up our religious community. A step towards rectifying this situation is the attempt to establish a women’s Beth Midrash…But the goal ought to be a Beth Midrash for both men and women… Jewish society will not survive if, for pseudo-religious reasons, we continue to deprive women of their due rights. This is the point at which we — those of us resolved to practice Torah — cannot perpetuate the halakhic decisions of our fathers dating from a social reality which differed radically from our own.”**

Reading these words only days after receiving rabbinic ordination from a co-ed Orthodox semikha program, I am extremely grateful to live in this time and to be part of the women’s Torah revolution.

I only hope that I am up to the task.

Blessed is God, Our Lord, King of the Universe, who has given us life and established us and brought us to this moment.

This article was originally published in the Times of Israel.

*Translation based on the Metsudah Siddur by Rav Avrohom Davis, via Sefaria

**Yeshayahu Leibowitz,” Judaism, Human Values, and the Jewish State,” ed. Eliezer Goldman (Cambridge: Harvard University Press 1992), 130, 131. It should be noted that Dr. Yeshayahu Leibowitz’s views on women’s involvement in public prayer rituals was more complicated.

Shayna Abramson, a part-Brazilian native Manhattanite, studied History and Jewish Studies at Johns Hopkins University before moving to Jerusalem. She has also spent some time studying Torah at the Drisha Institute in Manhattan, and has a passion for soccer and poetry. She is currently pursuing an M.A. in Political Science from Hebrew University, and is a rabbinic fellow at Beit Midrash Har’el.